Political Descent. Malthus, Mutualism and the Politics of Evolution in Victorian England.

It is well known that Darwin’s theory of natural selection was inspired by Thomas Malthus’s famous Essay on the Principle of Population. Darwin not only acknowledged this in Origin of Species, noting that “it is the theory of Malthus applied with manifold force to the whole animal and vegetable kingdoms”, but recalled the moment when the significance of Malthus’s work first struck him in his autobiography:

“In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic enquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population, and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work”.

It was shortly after his return from his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle in 1836 that Darwin read Malthus. He had been putting in long hours writing up his geological notes, but had been developing his theory of evolution in the few spare moments he could find. Darwin was working up an answer to that “mystery of mysteries”, as it had been called, the origin of new species. Naturalists and mineralogists had long been pulling strange and wonderful beasts out of the ground in fossil form, and they needed an explanation. Darwin was already familiar with Malthus’s ideas; for even though Malthus had originally developed his controversial political economy in the late eighteenth century, Malthusian economics were going through a renaissance in the 1830s. Malthus had made the case that in society, just as in nature, there would never be sufficient food for everyone to live in luxury, indeed, he had argued that there would always be those who went hungry.

The politics of Malthus’s position were evident to all. He had written his essay in an attempt to undermine what he believed to be the unrealistic Enlightenment ideals of universal progress and prosperity, and had received harsh criticism from political radicals for his troubles. “An apostle of the rich,” the poet Robert Southey had called him, both amazed and affronted at the “stupid ignorance of the man”; the essay was “Adam Smith’s book in code, a confession of faith in this system; a tedious and hardhearted book.” Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations had long been the bible of liberal political economy, and Malthus was read as furthering those interests.

Indeed, half a century later, far from being decried Malthus’s work was embraced by a new generation who saw the notion that individuals should have to struggle to make their way in a competitive world as speaking to their own times. In the context of the industrial revolution, and of a rising middle class of industrialists and entrepreneurs, the values of hard work, thrift and economic independence prevailed; the suggestion too that the poor were responsible for their own plight made Malthus appear all the more emblematic of the times. Historians have long noted that Darwin’s theory of natural selection not only echoed, but endorsed the Whig politics of industrial England, and this, I would contend, was a large part of why evolution was accepted in England as quickly as it was. Indeed, while both historians and the public have often been led by their present preoccupations to focus upon the religious implications to Darwin’s work, a full consideration of the many and diverse responses to the publication of Origin shows that evolution was read by contemporaries as having as much to say about politics as to theology.

Thomas Huxley, the young and talented naturalist who would later make his name as “Darwin’s Bulldog”, and who has long been regarded as one of the most significant scientists of the nineteenth century, welcomed Darwin’s work in an early review, but did so not only as a major contrition to an important scientific question, but at the same time as “a veritable Whitworth gun in the armoury of liberalism”. The analogy was telling of his enthusiasm. The Whitworth, developed by Sir Joseph Whitworth, had hexagonal rifling, and far exceeded the Enfield, which had long been the standard service rifle of the British army, in both accuracy and range. To Huxley’s mind, like the Whitworth, Darwin’s theory was not only the best available answer to the species question, but was certainly unanswerable by the creationist ‘natural theology’ offered by more conservative thinkers. Huxley was not alone in his recognition of the politics of natural selection. Although from another perspective, the noted socialist Karl Marx also thought that Darwin’s book read like capitalist apologetics. Writing to his friend and long-time supporter Friedrich Engels, he made the following observation:

“It is remarkable how Darwin rediscovered, among the beasts and plants, the society of England with its division of labor, competition, opening up of new markets, ‘inventions,’ and Malthusian ‘struggle for existence.’ It is Hobbes’ bellum omniun contra omnes…” [war of all against all].

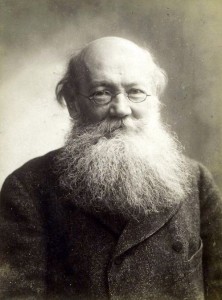

Here I should say that none of this is particularly new to historians, although as I have mentioned, – and certainly in the US – the emphasis tends to be on the religious implications of evolution. However, what it clear is that there is also an important story to tell here about the politics of evolution. From what I have said already, one might assume that this would be the familiar story of social Darwinism: that Darwin’s work was read – and possibly written – as an endorsement of the ruthless economic competition of laissez-faire capitalism. This has certainly been the dominant theme of the majority of the existing work in the field. This would only be a part of the story, however, as this view of life, and of the Origin of Species, was only one among many. Notably, and what historians have allowed to go largely unrecorded, is the fact that there was a significant and vocal population who embraced both evolution and the Origin as a vindication of a very different politics, one based upon cooperation and mutual aid. I say largely unnoticed, because historians have certainly noticed the existence of Peter Kropotkin’s work on mutual aid as a factor in evolution (among the best is Mark Borrello’s account in his book Evolutionary Restraints, which I reviewed on this blog some time ago), which was published throughout the 1880s and 1890s, but they have not recognized that Kropotkin was one among many who embraced a mutualist reading of Origin to support and substantiate their own more socialistic politics. And this is where my new book comes in.

In Political Descent. Malthus, Mutualism and the Politics of Evolution in Victorian England I show that in fact the politics of evolution were very much more contested than historians have hitherto recognized. Kropotkin was not a lone socialist voice in a capitalist wilderness, but rather was representative of an entire tradition of men and women who were interested in what the fact of our evolution had to say about the kind of creatures we are, and thus about the kind of society that it might be possible for us to live in.

What I think many people will find compelling about this story is that, just as Kropotkin argued was the case in the last years of the nineteenth century, it is clear that Darwin was much more sympathetic to those who saw mutualism and cooperation as the hallmarks of what had made humans ‘fit’ in the struggle for existence, than either Huxley or Marx thought. Indeed, and as Kropotkin had sought to point out to his readers, Darwin had said as much in the 1871 book The Descent of Man in which he had tackled human evolution head on. By the 1870s, the most important question about the evolution of mankind had become the origin of mind, morals and conscience. These apparently uniquely human characteristics were the last bastion of a ‘human exceptionalism’ among those who still sought a role for the divine in origin of man. After all, if the world worked to favour only the most competitive individuals, then it seemed logical that any resources invested in helping others survive would only weaken the altruistic. If generosity and altruism were not a divinely inspired character, however, conventional accounts of the origin of human morals emphasized the benefits that might accrue to the apparent altruist by pursuing a course of self-interest. This again would fit with the politics of liberal political economy. Darwin, though, was of a different mind. By providing a naturalistic account of the evolution of these highest of human qualities, one grounded in a history of the evolution of genuinely altruistic regard for others, Darwin sought to undermine the rampant individualism that others were using his own work to support. “Thus the reproach of laying the foundation of the most noble part of our nature in the base principle of selfishness is removed”, he wrote.

Piers J. Hale’s book Political Descent. Malthus, Mutualism and the Politics of Evolution in Victorian England was published by Chicago University Press in 2014.